17th century concept of consciousness

Consciousness (derived from the Middle High German word bewissen in the sense of “having knowledge of something”,[1] Latin _conscientia_ “co-knowledge” and Ancient Greek συνείδησις syneídēsis “co-appearance”, “co-image”, “co-knowledge,” συναίσθησις _synaísthēsis_ “co-perception,” “co-feeling,” and φρόνησις phrónēsis from φρονεῖν phroneín “to be in one’s senses, to think”) is, in the broadest sense, the experience of mental states and processes. A generalized definition of the term is difficult due to its various uses with different meanings. Scientific research is concerned with definable properties of conscious experience.

Meaning of the term consciousness

The word “consciousness” was coined by Christian Wolff as a loan translation of the Latin conscientia.[2] The Latin word had originally meant conscience and had first been used in a more general sense by René Descartes. In linguistic usage, the term consciousness has a very diverse meaning, which partly overlaps with the meanings of mind and soul. In contrast to the latter, however, the term consciousness is less determined by theological and dualistic-metaphysical thoughts, which is why it is also used in the natural sciences.

It complicates many discussions that consciousness basically has two meanings.[3] The first is that we perceive something and are awake and aware. The second, that we perceive or do something consciously, that is, we focus our thoughts on what we are doing. Further, consciousness is not a dual characteristic that one has or does not have. There are nuances, depending on the definition. Michio Kaku defines it this way, “Consciousness is the process of creating a model of the world using numerous feedback loops regarding various parameters (e.g., temperature, space, time, and in relation to each other) to achieve a goal.” He distinguishes 4 levels of consciousness, from plants to humans – depending on the number of feedback loops increasing exponentially from level 0 to level 3.[4]

Today one distinguishes different aspects and stages of development in philosophy and natural science:

- Consciousness as “animated-being” or as “inspired-being” in different religions or as the unlimited reality in mystical realms.

- Being conscious: Means the awake-conscious state of living beings, which is distinguished from the state of sleep, unconsciousness, and other states of consciousness, etc. In this sense, consciousness can be narrowed down by observation or experience. Many scientific researches started here; especially with the question how are the brain and consciousness connected.

- Consciousness as phenomenal consciousness: a living being that possesses phenomenal consciousness not only takes in stimuli, but also experiences them. In this sense, one has phenomenal consciousness when, for example, one feels pain, is happy, perceives colors, or is cold. In general, animals with sufficiently complex brain structure are thought to have such consciousness. Phenomenal consciousness has been addressed in philosophy of mind as a qualia problem.

- Access consciousness: a living being that has access consciousness has control over its thoughts, can make decisions, and can act in a coordinated manner.

- Consciousness as mental consciousness: A living being that has mental consciousness has thoughts. So, for example, one who thinks, remembers, plans, and expects something to be the case has this consciousness. In the philosophy of mind, it has been addressed as the problem of intentionality.

- Consciousness of the self: Self-consciousness in this sense is possessed by living beings who not only have phenomenal and mental consciousness, but are aware that they have such consciousness.

Individual consciousness is possessed by those who are aware of themselves and their uniqueness as living beings, and they perceive the uniqueness of other living beings. It is found in humans and, to some extent, in the behavior of some other mammalian species.

The use of the term consciousness usually depends on one of these meanings, limits it. Also, different worldviews are often expressed in the various usages.

Consciousness in philosophy

Consciousness as a puzzle

In a materialistic worldview, the mystery of consciousness arises from the question of how in principle it can be possible for the idea of consciousness to arise from a certain arrangement and dynamics of matter.

In a non-materialistic worldview, no statement about consciousness can be derived from knowledge of the physical properties of a system. Here it is assumed: Even if two different living beings A and B were in exactly the same neurophysiologically functional state (which is completely known to scientists), A could be conscious while B is not. The theoretical possibility of such a “zombie” is highly controversial among philosophers.

According to philosophical thoughts, a human being could function in exactly the same way as he does now, without being conscious of it (see: Philosophical Zombie). In the same way, a machine could behave exactly like a human being without being attributed consciousness (see: Chinese Room). The imaginability of these situations reveals that the phenomenon of consciousness is not yet understood from a scientific point of view. And finally, in contrast to other problems, it seems to be unclear on the basis of which criteria a solution to the problem could be recognized.

Inner perspective and outer perspective

The inner perspective in an illustration by Ernst Mach

In philosophy, the mystery of consciousness has been known for a long time. However, it was largely forgotten in the first half of the 20th century under the influence of behaviorism and Edmund Husserl’s critique of psychologism. This changed with Thomas Nagel’s 1974 essay “What is it like to be a bat?” (Wie ist es, eine Fledermaus zu sein?). Nagel argued that we would never know what it felt like to be a bat. These subjective ideas, he argued, could not be explored from the outside perspective of the natural sciences. Today, some philosophers share the enigmatic thesis – for example, David Chalmers, Frank Jackson, Joseph Levine, and Peter Bieri, while others see no enigma here—for example, Patricia Churchland, Paul Churchland, and Daniel Dennett.

The mystery of consciousness manifests itself in two aspects: _On the one hand_, states of consciousness have experiential content. However it is not clear how the brain can produce experience. This is the qualia problem. On the other hand, thoughts can refer to empirical facts and are therefore true or false. However, it is not clear how the brain can produce thoughts with such properties. This is the intentionality problem.

Internal perspective and external perspective

A distinction is often made between two approaches to consciousness. On the one hand there is an immediate and non-symbolic experience of consciousness, called introspection. On the other hand, one describes consciousness phenomena from the external perspective of the natural sciences. A distinction between the immediate and the symbolically mediated mode of observation is understood by many philosophers, even though some theorists and theologians have sharply criticized the concept of the immediate and private interior. Baruch Spinoza, for example, calls immediate, non-symbolic contemplation “intuition” and the capacity for symbolic description “intellect.”

It is sometimes claimed that the level of immediate experience of consciousness is the decisive one for the knowledge of reality. Only in it is the core of consciousness, the subjective experience, accessible. However, since this level is not directly accessible by an _objective_ description, there are also limits to the scientific knowledge in the field of consciousness.

Consciousness, materialism and dualism

The consciousness-related anti-materialist arguments are mostly based on the concepts of qualia and intentionality discussed above. The arguments are as follows: If materialism is true, then qualia and intentionality must be reductively explainable. But they are not reductively explainable. So materialism is false. In the philosophical debate, however, the argument becomes more complex. A well-known argument comes from Frank Cameron Jackson. In a thought experiment there is the super scientist Mary, who grows up and lives in a black and white laboratory. She has never seen colors and therefore doesn’t know what colors look like. However, she knows all the physical facts about color vision. But since she doesn’t know all the facts about colors (she doesn’t know what they look like), there are non-physical facts, she says. Jackson concludes that there are non-physical facts and that materialism is false. Various materialistic rejoinders have been made against this argument (see Qualia).

Numerous materialist replicas have been developed against such dualist arguments. They are based on ways of responding to the concepts of qualia and intentionality described above. Thus, a variety of materialist concepts of consciousness exist. Functionalists such as Jerry Fodor and the early Hilary Putnam wanted to explain consciousness in analogy to the computer through an abstract, internal system structure. Identity theorists such as Ullin Place and John Smart wanted to trace consciousness directly to brain processes, while eliminative materialists such as Patricia and Paul Churchland classified consciousness as an entirely useless concept. For more detailed descriptions, see the article Philosophy of Mind.

Consciousness in the natural sciences

Overview

Experience triggers behavior, and neural processes can be simulated on a computer, as shown by neuroscience. This field of work is artificial intelligence. Many individual sciences are involved in the study of consciousness, since there are a large number of different phenomena that can be described empirically.

Neuroscience

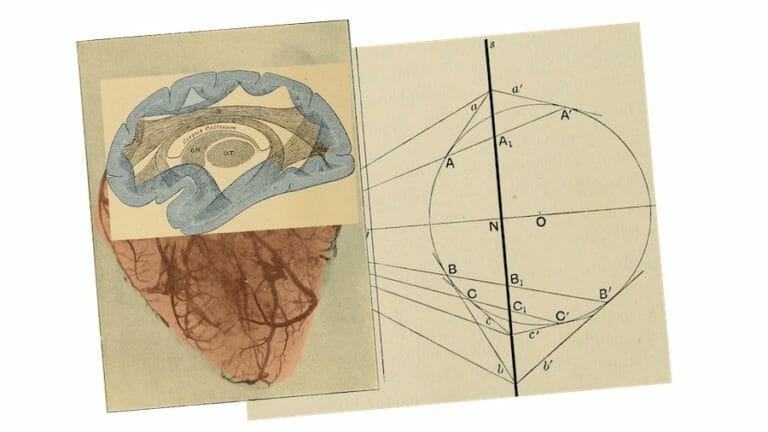

A brain visualized by imaging technique

In neuroscience, one of the topics being investigated is the connection between the brain and consciousness. Neuroscientist António Damásio defines consciousness as follows: “Consciousness is a state of mind in which one has knowledge of one’s own existence and the existence of an environment.”[7]

A central element of the neuroscientific study of consciousness is the search for neural correlations of consciousness. One tries to contrast certain mental states with neuronal processes.[8] This search for correlations is helped by the fact that the brain is structured functionally. Different parts of the brain (areas) are responsible for different tasks. Thus, it is assumed that Broca’s center (or Brodmann’s areas 44 and 45) is responsible for speech production. Damage to this region often leads to a speech disorder called Broca’s aphasia.[9] Measurements of brain activity during speech production shows increased activity in this region. Furthermore, electrical stimulation of this area can lead to temporary speech problems. Assignments of mental states to brain regions are almost always incomplete, however, because stimuli are usually processed simultaneously in multiple brain regions they are rarely recorded in their entirety.

The conceptual and methodological distinction between neural correlates of consciousness and unconscious brain activity makes it possible to investigate which neural processes are coupled to awareness of an internal state and which are not. During deep sleep, anesthesia, or some types of coma and epilepsy, for example, large parts of the brain are active without being accompanied by conscious states.

In recent years, perceptual research has taken a dominant position within basic neurobiological research on consciousness. Some visual illusions, for example, allow us to investigate how the conscious experience of the sensory world is related to the physical processes of stimulus reception and processing. A prime example is the phenomenon of binocular rivalry, in which an observer can consciously perceive only one of two simultaneously presented images. Neuroscientific research on this phenomenon has shown that large parts of the brain are activated by visual stimuli that are not consciously perceived. On the other hand, humans experience themselves as conscious even when their sensory perception and attention are extremely reduced, such as during a lucid dream phase. Therefore, brain research has not yet satisfactorily answered what the peculiar state of being conscious consists of in humans.

The determination of brain activity indicating conscious experience is of increasing ethical and practical importance. Several medical problem areas, such as the possibility of temporary intraoperative wakefulness during general anesthesia, the classification of coma patients and their optimal treatment, or the question of brain death are directly affected by this.

Psychology

Consciousness is a central concept for psychology. It is, on the one hand, the totality of experiences, i.e., the experienced mental states and activities (ideas, feelings, etc.), and, on the other hand, consciousness as a special kind of immediate awareness of these experiences, which is also called inner experience.[10] Phenomenal consciousness and access consciousness are of utmost importance, since the two phenomena include perceiving, thinking, and deciding. In addition, the distinction between conscious and unconscious is important. In cognitive psychology, both are poles of knowledge of what is present and its communicability where many degrees of clarity related to intention (action design), concentration, critical self-reference, alertness, prior experience, classification, discrimination, and affect strivings. Consciousness.[11]

There are some psychological approaches that contribute to consciousness research:

- Information processing approach: this conceives of humans as information-processing systems, that is, humans take in information from their environment, process it, and then exhibit certain behavior. Consciousness is identified with a particular processing mechanism. In the information processing approach, mental processes are viewed from an external perspective. However, consciousness is dependent on the particular subject and exists in the internal perspective. Therefore, one must critically consider whether the objective approach can explain subjective experience.[12]

- Working memory model (Baddeley): this model assumes that there is a short-term memory and a higher-level control system in the human brain, which is called the central executive. Access consciousness is said to be the function of the central executive. Phenomenal consciousness cannot be equated with the contents of short-term memory. In this, up to 7 chunks can be maintained and stored in the short term, but only 3 chunks can be phenomenally conscious to a person. Phenomenal awareness arises in interaction with selective attention. Only that information in short-term memory to which attention is directed becomes phenomenally conscious to a person.[13]

- Controlled processes model (Snyder and Posner): the model distinguishes controlled processes from automatic processes. Automatic processes are unconscious, fast, non-intentional, and do not interfere with other processes, while controlled processes are conscious, slow, intentional, and limited in capacity. Access consciousness exists when a process is controlled. Automatic processes are also subject to cognitive control; however, this control occurs before the process itself and is therefore distinct from controlled processes.[14]

- DICE (dissociable interactions and conscious experience) model (Schacter): this model distinguishes explicit, conscious from implicit, unconscious memory phenomena. The name of the model comes from the fact that Schacter assumes that there is dissociation between conscious experience and behavioral efficacy. In Schacter’s model, procedural knowledge that influences behavior is acquired phenomenally unconsciously, and factual knowledge is learned consciously. Schacter believes that there is a CAS (conscious awareness system_) in the human brain that is connected to all processing modules and therefore can be compared to a global database. The CAS also contains the conscious experiences. Phenomenal consciousness consequently arises only when the memory content of a processing module activates the CAS. Phenomenal consciousness is a prerequisite for access consciousness. Only when memory content is phenomenally conscious can the executive system be activated.[15]

The psychological approaches can be criticized for not answering the question of by which mechanisms or processes in the brain does phenomenal consciousness arise. This criticism applies to all approaches that describe phenomenal consciousness as the presence of a mental representation in a particular system. Psychology to date has no theory that can explain how and why phenomenal consciousness is related to mental representations.[12]

Consciousness in animals

Primate research has found out a lot of amazing things about the mental abilities of monkeys.

One topic that has gained popularity in recent decades is the question of possible consciousness in other living beings. Various disciplines are working on its study: ethology, neuroscience, cognitive science, linguistics, philosophy, and psychology.[22]

For example, dogs, like all more highly evolved animals, can feel pain, but we don’t know to what extent they can consciously process it because they cannot communicate such conscious processing. This requires brain structures that can process linguistically conceived ideas. This has been partially observed in chimpanzees, which can learn sign systems, and gray parrots, for example.\[23]\[24] Gradualism, which seems to be the most plausible position, tests each species to determine what states of consciousness it can have. This is particularly difficult in the case of animals, which have perceptions that are very different from those of humans.[25]

For a long time it was assumed that ego-consciousness occurs only in humans. In the meantime, however, it has been proven that other animals, such as chimpanzees, orangutans, rhesus monkeys, pigs, elephants, dolphins and also various corvids can recognize themselves in the mirror, which according to a widespread view could be a possible indication of reflective consciousness.\[26]\[27][28] A gradualism regarding the existence of consciousness does not face the problem of clarifying where consciousness begins in the animal kingdom. Rather, it is concerned with describing as accurately as possible the conditions and limitations of consciousness for each individual case.

Experiments by a group of researchers led by J. David Smith indicate that rhesus monkeys are capable of metacognition, that is, of reflecting on their own knowledge.[29]

Consciousness in religions

In the context of religious ideas of a soul and a life after death (see e.g. Judaism, Christianity and Islam) the concepts of spirit (of God) and soul play an essential role in the understanding of consciousness. According to this, human consciousness cannot be understood and explained – as attempted by the sciences – solely as a product of nature or evolution, but exclusively in connection with a transpersonal or transcendental spirituality. It is this divine spirituality which – like everything naturally animated—also “makes alive” or “animates” the consciousness, i.e. enables the human I-perception.

In the Tanach it is said that the “rûah” (Hebrew word for spirit, or synonymously used in connection with “næfæsch”, soul) breathes life into the creature. It exercises the vital functions of a spiritual, will and religious nature. In the New Testament it is explained that the body comes to life only through the spirit of God. For example, it states: “It is the Spirit (of God) that gives life; the flesh profits nothing” (John 6:63 EU). For Paul, the distinction between the kingdom of the Spirit (cf. eternal I) and the kingdom of the flesh (mortal nature) was central. The same wisdom is found in the Quran, where it is said, for example, that God breathed into Adam of his spirit (cf. Arabic word _rūh روح / rūḥ_) and thus gave him life (Sura 15:29; 32:9; 38:72). In the doctrinal system of the Basrian Muʿtazilite an-Nazzām (st. 835-845), the spirit is depicted as a form or being that mixes with the body like a gas and permeates it to the fingertips, but at death breaks away from this connection again and continues to exist independently (cf. “eternal I”).[30]

In Christianity, the terms soul and spirit (also “Holy Spirit”) are sharply distinguished from the spirit of man. This results from the fact that the former terms are closer in their meaning to the metaphysics of classical Christian fundamental theology and philosophy: Namely, they suggest the existence of a non-material carrier of states of consciousness. Nevertheless, the concept of consciousness plays a role in modern Christian debates. This happens, for example, in the context of proof of God. Thus, it is argued that the interaction between immaterial states of consciousness and the material body can only be explained by God or that the internal structure and order of consciousness in terms of the teleological proof of God suggests the existence of God.

Various Buddhist traditions and Hindu schools of yoga have direct and holistic experience of consciousness as their focus. With the help of meditation or other exercise techniques, certain states of consciousness would be experienced by removing personal and social identifications. A special distinction is made to consciousness, which means a full awareness of the momentary thinking and feeling. It should be achieved through the practice of mindfulness. Insights into the nature of consciousness are gained through one’s own experience, which goes beyond a purely reflective and descriptive approach. The concept of separation of body and mind or brain and consciousness is experienced as a design of thought. In general, all mystical-esoteric directions in religions (e.g. Gnosticism, Kabbalah, Sufism, etc.) want to bring about a change in the consciousness of man. In fact, neuro theological research using imaging techniques shows that unusual neural activity patterns and even neuroanatomical changes can result from many years of meditation practice.[31]