Being human is amazing! We have the choice to develop our own interests, talents and curiosities as we travel through life. We can use our brains to learn, and these cognitive skills can be built on further if we choose to do so. We have access to almost limitless amounts of information at the touch of a button or a screen swipe and many of us have a lifestyle that earlier generations would have been amazed at. And yet, we are living in a world where there is a growing dissatisfaction and sense of lost meaning. An increased number of people report mental health issues and many are lonely, often through a disconnection within relationships and society. The recent global pandemic showed us how we thrive when we are connected and struggle when we are not. In a world where we have championed the brain, we are finding out that it is our heart that gives us a truer quality of life, meaning and connection, and that a denial of this causes us to suffer.

The heart has long been associated with feelings of love; however, it has been relegated to a position of a lesser importance than that which the brain occupies. You could say that the heart has been the Robin to the Batman that is the brain. This is even though we are shaped by the behaviour of our hearts in our day to day lives. We have many idioms of speech which refer to the central importance of the heart. We ‘follow our hearts’, ‘get to the heart of something’ or ‘give wholeheartedly’, and we speak of being ‘heartbroken’, downhearted’ or being ‘heavy of heart’. Our heart may ’skip a beat’ when we fall in love with a romantic partner or where we meet our babies for the first time. We can also feel our hearts soar on hearing good or exciting news. Could these words be more than mere metaphors?

Over the last fifteen years Peter Granger has become more and more fascinated by the heart and its untapped power and created Heartbond. His experience as a counsellor had shown him that when clients healed or overcame a relationship issue that they felt better, and they often reported that their heart felt lighter. These feelings were accompanied by distinct physiological sensations. What could be happening? Lots of us can recognise the feeling of wellbeing when we are in a connected state and how this state reflects itself in our bodies and particularly in our hearts; however, could these things be measured? Peter decided to find out.

Working full time on this research project Peter identified that he would need some readily available heart rate monitors as well as an app to help gather and process data from two people simultaneously. No such app existed, so supported by freely available help from the internet, Peter taught himself to code, creating the Heartbond app which could measure the heart rate patterns of two people in real time. Many of the experiments have been carried out between Peter and me. We studied how our changing heart rate patterns synchronised when we were feeling love, appreciation and gratitude for each other. Of course, we also observed what happened when we were feeling less bonded.

For most of this time I was working full time within the leadership team of a primary school, whilst Peter dedicated himself to the research. It became clear that when Peter and I were connected to each other, when the feelings of love for each other were strong, then our heart patterns would synchronise in quite beautiful ways. Our patterns were very similar during the times of deep connection. When we were distracted or stressed, we found that these patterns showed little synchronisation. We also noticed that the synchronisation was accompanied by a feeling of positive connection which lasted far beyond the time of the experiments.

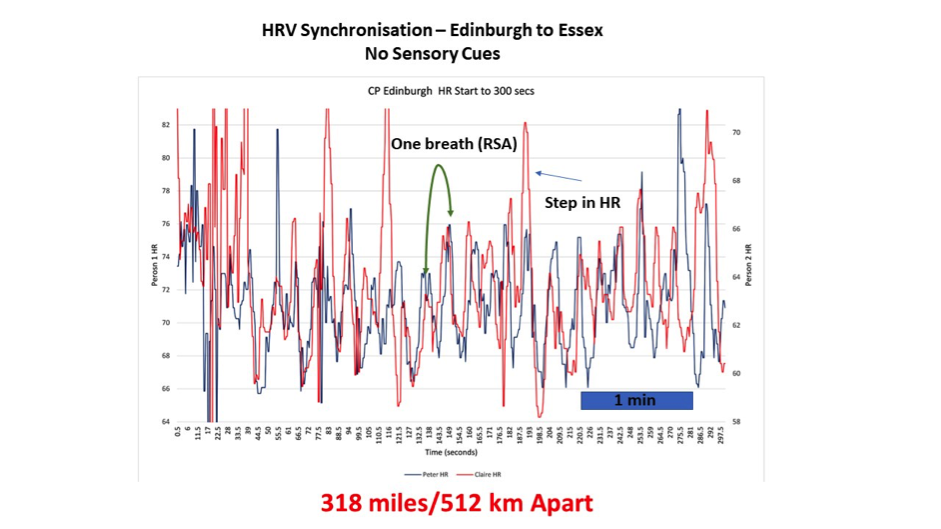

Once we had identified the effect that living in a bonded state had on our two hearts and confirmed that other researchers had observed the very same phenomenon, we decided to extend our research in a radical way. We did this because, out of interest, we ran a heart synchronisation experiment when we were both hundreds of miles apart. To our astonishment, what came out of this experiment was totally unexpected. Let me describe it in more detail. The experiment took place between Edinburgh, Scotland and Essex, England – we were 318 miles (512 km) apart. I was at home and Peter was lying on a bed in a hotel. We both wore heart rate monitors and recorded the data, having started the software at the same time. Importantly, apart from chatting on the phone to set up the start of the experiment, there were no communication devices operating during the experiment. We simply felt love for each other for twenty minutes and recorded our changing heart rates. When Peter got home from his trip, he plotted the data out and saw that the heart rate patterns were synchronising as if we had been in the same room at home. In creating this experiment, we had made sure that our physical senses could not have been involved in the synchronisation – we were just too far apart for that to be possible. Either there was a common environmental factor causing us to synchronise over this distance, or we must have been communicating energetically in some way with each other. We were to later probe the concept of an environmental factor, but we were both drawn to the conclusion that somehow our hearts, and the brain that they are attached to, can connect over large distances without conventional sensory communication.

Over the next few years, we continued to carry out our experiments, both locally and at a distance. This varied from a few metres to thousands of miles, on one occasion between England and California. In most of these cases we saw clear and statistically convincing correlation of our heart rate patterns when we felt love for each other. We also broadened our research to include other pairs of people, some of whom were known to each other and some who were strangers prior to the experiments. We carried out a couple of workshops in the southeast of England where we were supported by members of the HeartMath community – a group who were familiar with breathing and heart-centred meditation. At one of these research days two strangers volunteered to wear a heart monitor for much of the day including while they slept. When the data was reviewed it was easy to see from the synchronisation where the participants had spent attentive time together and also those times when they lost their focus on each other.

After several years researching we had carried out so many experiments between ourselves and others that we were in no doubt that being in a bonded relationship with another person, irrespective of the nature of that relationship, would lead to synchronisation of heart patterns. We knew that this level of connection leads to feelings of wellbeing and happiness. What was going to be our next step? Well, it was very important to me that we could experience the benefits of heart synchronisation and access it regularly in our daily lives. Working in a school and supporting staff and parents at difficult times, I was aware that if I opened my heart to someone, truly putting myself in their position, then we would have better and more constructive conversations than if I maintained my position of being the only one who was in the right. I began to realise that this might be happening when we talk to a friend, and they help us unburden ourselves from the troubles of life. When we walk away from times like these feeling uplifted, is it that our friend has literally changed our heart rate patterns for the better through their care and compassion?

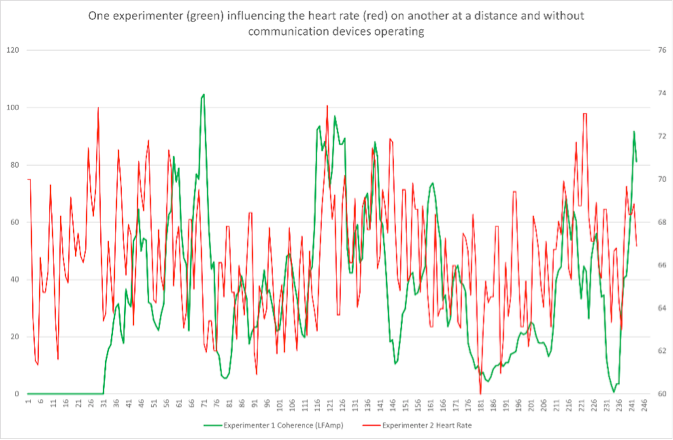

Peter had also been wondering whether our positive intentions could influence another person’s heart rate patterns directly, so together we moved into the next phase of our research. Most of the experiments that followed focused on Peter feeling love, appreciation and gratitude for me, while I was distracted, catching up on schoolwork. Using the real-time app, we were soon able to see the impact when Peter focused his loving attention on me. The experimental sessions were punctuated with marked periods where Peter focussed strong and loving intent on me and then distracted himself. Consistently this showed up in the data as joint peaks in our heart rhythms separated by periods of lost synchronisation. The ability to actively change another person’s heart rate patterns points to the presence of energetic communication in addition to our usual sensory communication. It also challenges the idea that it is the mutual sensing of environmental factors that is driving the synchronisation.

Having shown that there was an intentional effect in heart-to-heart synchronisation, we set out to test other couples, locally. We showed that the phenomenon was often observable in the relationships in which we tested intentional effects. At our conference in November 2023, during a live demonstration, I was able to influence the heart rate patterns of a volunteer who was 38 miles (61km) away and without any communication devices being operational.

I am sure you can appreciate that the implications and ramifications of our work are considerable. Could this be why talking to a therapist works? How could we improve our lives and the lives of those around us if we can harness the power of our open hearts? If we identify this ability in ourselves (one that we all have) could we resolve more issues and live more happily? Simply, does the heart have the capacity to transform our lives and our ability to thrive? We believe that it can.

Our experiments are easy and cheap to run so our research results can be easily replicated by the scientific community. This ground-breaking knowledge could herald the dawn of a new era in relationship building – one that is built on the heart and its capacity to love unconditionally. We are ordinary people, and what we have done is available to anybody who understands how important their heart is and how it is key to living a happier and more fulfilling life. We invite you to open your own heart and start connecting!

About

Background: Peter Granger and Claire Berry are partners in life and work together running Heartbond. You can find us at: www.heartbond.co.uk

You can find a video of Peter’s talk from the BIGHEART 2023 conference here:

Artist

Multicolor illustrations of animals and sea creatures from Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature) by German zoologist, naturalist, professor, and marine biologist, Ernst Haeckel (1843–1919), in full Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckela. Haeckel was known for discovering and naming thousands of new species. Kunstformen der Natur was known for bridging the gap between science and art. www.rawpixel.com